[My

last post, “Responses to ‘Yes . . . But Is It Art?’” (published on Rick On Theater on 8 April),

was an assemblage of articles, letters, and reviews published in the New

York Times in response to Morley Safer’s broadcast on 60 Minutes on

19 September 1993. The subject of the

CBS News segment was, as readers of ROT will know, he state of art at

the end of the 20th century (and, by implication, the beginning of the 21st).

[As I said when I posted the transcript of that 60 Minutes report (“‘Morley Safer’s Infamous 1993 Art Story,’” 2 April), Safer’s opinions raised he disapprobation of many in the art world, from art-lovers and collectors, to artists, to dealers, to critics and academics. I promised to post some of that conversation—in some cases, admonitions—which is what the last post started. This is the second installment of that part of this short series, covering the commentary from other outlets from across the country.]

“YES . . . BUT IS IT ART?:

by Louis Torres and Michelle Marder Kamhi

[This article first appeared in Aristos, a website that styles itself an online review of the arts and the philosophy of art, in June 1994. (I made reference to it briefly in the afterword to “Morley Safer Defends His Take On Contemporary Art,” 5 April.)]

Twice in the past year, millions of American viewers had the pleasure of seeing the contemporary art establishment get its comeuppance on prime-time network television.

First, there was the segment entitled “Yes . . . But is it Art?” last September 19 on the long-running CBS newsmagazine 60 Minutes, which exposed the fraudulence of the contemporary work hyped by most dealers, critics, and curators—work ranging from so-called abstract art to a “piece” consisting of two basketballs submerged in a fish tank. Morley Safer, the intrepid reporter for the segment, aptly derided the art world’s impenetrable Artspeak, and deprecated the status-seeking collectors of such work by invoking the old adage “There’s a sucker born every minute.”

Four months later, on the January 17 [1994] episode [“The Deal of the Art“] of CBS’s popular Murphy Brown show, the sit-com’s fictional TV anchorwoman also mocked the fashionable art world, including its pseudo-artists. Undoubtedly inspired by the 60 Minutes segment and its aftermath, the Murphy Brown episode was as trenchant a social satire as any play by Molière—a witty denuding of intellectual pretension and charlatanry.

In one scene, Murphy, facing off against art “experts” on a PBS talk show (a scene modeled on Morley Safer’s appearance on the Charlie Rose show), ridiculed a work entitled Commode-ity, which was nothing more than an actual toilet affixed to a wall. The sit-com writer did not exaggerate. Commode-ity was no more bizarre than the real-life commodities of the postmodernist whose “artworks” consisting of urinals and sinks had been featured on 60 Minutes—or than the urinal that the early modernist Marcel Duchamp presented in 1917 as an artwork entitled Fountain.

[In reality, Duchamp never “presented” Fountain in the sense that he displayed it. It was rejected by the board of the Society of Independent Artists, for whose exhibition he submitted it. After that, it was lost and never seen in public. He had had Fountain photographed, which is why pictures of it are often published—and how reproductions of the original piece have been exhibited.]

In another scene, equally true to life, Murphy succeeded in passing off as a mature work by an unknown artist a painting by her eighteen-month-old son. The scene might well have been inspired by an event reported in the Manchester Guardian in February of last year [10 February 1993]. According to the Guardian, a “blob”-like painting by a four-year-old child was bought by a collector for £295 [$753 today] after being exhibited in the annual show of the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts. The child’s mother had submitted the work as a joke, and a panel of six experts, unaware of the age of the “artist,” had selected it because they thought it displayed “a certain quality of colour balance, composition and technical skill.”

In the final analysis, real life has been less satisfying than the sit-com, however. There is no reason to hope, for instance, that the Manchester Academy of Fine Arts will soon alter its selection criteria. When informed that a work by a four-year-old had been exhibited, the president of the academy was unperturbed. “The art of children often has a very uncluttered quality which adults often strive to gain,” she explained to BBC Radio 4, “so I don’t feel in the least embarrassed about it.” She then added, without flinching at the implicit contradiction of her expert panel’s judgment of the qualities they discerned in the work: “Technical skill can get in the way of instinctive response.”

Closer to home, the heated media debate that followed the airing of “Yes . . . But Is It Art?” on 60 Minutes fizzled out in a series of ill-considered letters by Morley Safer to the New York Times and other periodicals, and in his ineffectual sparring with Artspeak experts on the Charlie Rose show [see “Morley Safer Defends His Take On Contemporary Art”]. Safer lost the debate, not because the purported experts’ arguments made any sense but because he, despite the best of intentions, had no consistent argument at all.

In contrast, Murphy Brown prevailed, through witty barbs and an unshakable confidence in her own common sense. In a triumphant moment, Murphy’s co-anchor had earlier declared: “People have been waiting for someone to blow the whistle on this so-called art and the business that feeds on it. It’s a house of cards, and perhaps your piece will help bring it down.” As another of Murphy’s colleagues observed, she had won allies even among viewers who generally disagreed with her stance on other issues. Clearly, the question of what art is cuts across customary political and social lines.

Nevertheless, it will take far more than an exposé on 60 Minutes or an episode of Murphy Brown to topple this house of cards. Too much money and prestige are invested in it for its proponents to yield without a fierce struggle. Major cultural institutions and corporate sponsors—not to mention countless “artists,” dealers, collectors, curators, and critics—have their fortunes and reputations at stake.

What is needed to sweep the art world clean is not merely an intuitive sense of what art isn’t, but a well-reasoned and clearly articulated understanding of what art is. Unfortunately, one cannot look to the majority of today’s academic philosophers of art for guidance. The profession, by its own admission, is in a state of confusion on this question, owing in part to the on-going proliferation of what it euphemistically refers to as “unconventional” art forms. Indeed, the American Society for Aesthetics lamented in a winter 1993 position paper that the central question of esthetics—What is art?—has become “increasingly intractable,” with the result that the very viability of the field as a philosophic discipline is in jeopardy.

Because philosophers have shrunk from defining the concept, the terms “art” and “artist” are up for grabs. It has even become common for critics to resort to such absurdly circular propositions as “If an artist says it’s art, it’s art” (Roberta Smith in the New York Times [“It May Be Good But Is It Art?,” 4 September 1988]) and “Dances are dances and ballets are ballets simply because people who call themselves choreographers say they are” (Jack Anderson, also in the Times [“Just What Is This Thing Called Dance?” 12 August 1990]).

One thing is certain, however, and cannot be repeated often enough. Art, like everything else in the universe, has an identity, which can be objectively defined. An essential attribute of art, we maintain, is meaning—objective and readily discernible meaning. If a work makes no sense at all to an ordinary person without the intervention of an expert, it is outside the realm of art.

That this fundamental truth was conveyed, albeit implicitly, on two of America’s most popular television programs bodes well indeed for the future.

[I can’t say that I agree with Torres and Kamhi’s last statement, in their final two paragraphs above. As for “meaning” being the “essential attribute of art,” I stand with Suzanne Langer (1895-1985), an art philosopher such as those Torres and Kamhi disparage.

[Langer wrote that art is symbolic language and “has no vocabulary, no dictionary definitions. It is . . . an expression of non-discursive thought.” “Beauty,” she said, “is expressive form.” In other words, beauty is a function of the artwork’s main purpose: if the work successfully expresses feeling, that is, “may truly be said to ‘do something to us,’” it is by definition ‘beautiful’—whether or not it’s also pretty.

[Langer

says nothing about “meaning.” What a

piece of art “means” to any given viewer depends on what it makes her or him

feel, and that could be thousands of different “meanings”—or none at all. (See

“Susanne Langer: Art, Beauty, & Theater,” 4 and 8 January 2010.)]

* *

* *

“JERRY SALTZ ON

MORLEY SAFER’S FACILE 60 MINUTES ART-WORLD SCREED”by Jerry Saltz

[Jerry Saltz is the senior art critic for New York magazine, which published this column on 1 April 2012. (It also appeared on Vulture, the online platform of New York.) This review is of Safer’s second 60 Minutes broadcast on contemporary art, the one in 2012, “Art Market,” after he made the trip down to Miami Beach for the Art Basel art fair.]

Art is for anyone. It just isn’t for everyone. Still, over

the past decade, its audience has hugely grown, and that’s irked those outside

the art world, who get irritated at things like incomprehensibility or money.

That’s when easy hit jobs on art’s bad values appear in mainstream media. A

harmless garden-variety example aired tonight on CBS’s 60 Minutes (I

didn’t know it was on anymore), as Morley Safer went into high snark. Never

mind that he did virtually the same piece in 1993, beating up on institutions

like the Whitney [Museum of American Art in New York City] and mentioning some

of the same names with the same pseudo-knowingness. (I think he’s got an art

bromance brewing with Jeff Koons. This time, at least, he has nice things to

say about Cindy Sherman and Kara Walker.) As with that 1993 piece — which he

brought up repeatedly, crowing about its notoriety — Safer was on about art

fairs, artspeak, high prices, collecting as conspicuous consumption, Russian

oligarchs who throw money around, and the ugliness of the market: endemic stuff

we all know about and dislike.

In the days before cable TV and the Internet, the art world would get bent out of shape by such sniping. (I remember tittering when, shortly after the 1993 story aired, I spotted Safer downing free Champagne at a Whitney event. The cravenness!) Nowadays, Safer’s cynicism is a good sign: It even performs a service for the art world. He goes to the biggest fish-in-a-barrel scene around, Art Basel Miami Beach, to take a few shots, and (while publicizing the story the other day) complains that there are now “customers who just weren’t there twenty years ago.” He scornfully said, “Now you have China, Malaysia, India, Russia … seriously, Russia.” Ick! Rich people from Malaysia and Russia! (It’s like he’s trying to stop a posh men’s club from integrating. Oh wait, he recently did that, too.) The self-devouring service he performs is being a one-percenter going after other one-percenters. He’s hating art that only others like him pay much attention to. You go, Morley.

In tonight’s segment, Safer delivered cliché after cliché, starting with “the emperor’s new clothes.” Earlier in the week, he was moaning that contemporary art “lacks any irony.” (What has he been looking at these past 40 years?) He worried that the “gatekeepers of art” permit such bad work. He doesn’t know that there are no “gatekeepers” in the art world anymore, that it’s mainly a wonderful chaos. It’s like the scene in Apocalypse Now when Martin Sheen crosses into Cambodia and asks a soldier, “Who’s in charge here?” The soldier, unaware he’s in a place where old rules no longer apply, panics and replies, “I thought you were!” That’s Safer.

Rather than really looking at art, he’s focused on the distraction, on celebrity, cash, and crassness. Safer fails to see that cash simply does what other cash does and collectors basically buy what other collectors have already bought. He’s now doing the same thing: Spotting the obvious. It sounds like he doesn’t regularly go to scores of local galleries, big and small, parsing out what he sees, month by month, deciding on a case-by-case basis what works, what doesn’t, why. He’s not finding his own taste; all he’s doing is not liking what other people like himself like. Or maybe Safer is just what Colonel Kurtz, in Apocalypse Now [played by an obese Marlon Brando], calls “an errand boy, sent by grocery clerks, to collect a bill.”

Flacking for the piece on Friday, Safer told Charlie Rose and Gayle King, “Even Jerry Saltz says 85 percent of the art we see is bad,” adding that he’d suggest that it’s 95 percent. Whatever. I wanted to tell him that the percent I suggested doesn’t only apply to the present. Eighty-five percent of the art made in the Renaissance wasn’t that good either. It’s just that we never see it: What is on view in museums has already been filtered for us. Safer doesn’t get that the thrill of contemporary art is that we’re all doing this filtering together, all the time, in public, everywhere. Moreover, his 85 percent is different from my 85 percent, which is different from yours, and so on down the line until you get to Glenn Beck [conservative political commentator and media personality], who says everything is Communist. No one knows how current art will shake out. This scares some people.

The reason Safer isn’t able to have what he calls “an aesthetic experience” with contemporary art is that he fears it. It’s too bad, because fear is a fantastic portal for such experiences. Fear tells you important things. Instead, Safer is fixated on art that only wants to be loved. Most art wants attention, but there are many ways of doing this — from being taken aback by Andy Warhol’s clashing colors and sliding silk-screens to being stopped in your tracks by just a dash in a poem by Emily Dickinson. Art isn’t something that only wants love. It’s also new forms of energy, skill, or beauty. It’s the ugliness of Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Children. Often art is something we cross the street to avoid, something that makes us uncomfortable, that tells us things we don’t want to know, that creates space for uncertainty. Safer goes to the most hellish place on Earth to look for “an aesthetic experience,” then gets grumpy when he doesn’t have one. It’s clownish.

The art world now knows that the more time spent by the Safers out there shooting the wounded, the more time other emerging, on-going, subtler, and maturing art will have to take root before the next generation of Safers takes its aim. The longer these folks are distracted by being riled and right, the better. I understand that Safer makes watercolors of motel rooms or something. So he does have ideas about what art should be. Morley, I challenge you to curate a public New York show of 25 to 35 contemporary artists — those who have emerged since, say, 1985 — whose work you really approve of, plus a few examples of your own art. I promise to review it, fair and square. Deal?

* * * *

“MORLEY SAFER

HATED CONTEMPORARY ART.

HE ONCE SENT A BUNDLE OF THEM TO ME”

[On 20 May 2016, five days after Safer retired from CBS after 50 years with the network and 46 years with 60 Minutes, and the day after the newsman’s death at 84, Saltz published this column, a sort of obituary. He had mentioned Safer’s painting in his 2012 article above; now he had a first-hand experience with it.]

Morley Safer, the legendary TV newsman, died Thursday at age 84. So why am I, an art critic, writing about him? Like a lot of people in the art world, I feel I have a sort of history with him.

I don’t mean to be speaking ill of the dead instantaneously, and I intend this more as a begrudging compliment: To us, Safer was a persistent pain in the ass, most famously in his September 1993 quarter-hour hit piece for 60 Minutes on the whole culture of contemporary art, snidely titled “Yes, But Is It Art?” In the segment, which quickly became insider shorthand for all the ways the wider world misunderstands and sometimes disdains contemporary art, the irascible Safer — dressed in an almost-tuxedo and dripping with disdainful innuendo that implied that all of this was just a sham — attacked high prices (or what seemed then like high prices), the infamous “political” Whitney Biennial, and, of course, Jeff Koons. And even though every potshot he took seemed slanted, one-sided, his arch insinuations got under the art world’s skin — a sign of different times, I guess, both for art and for television news. I remember how miffed I was when, two weeks after his hatchet job hit the airwaves, I spied him drinking free Champagne at that season’s Whitney Museum benefit dinner. In 2012 he more or less repeated the drive-by, sauntering down the aisles of one of the grossest souks on Earth, the Art Basel Miami Beach Art Fair, for another segment, all the while drolly pointing to this or that fashion victim or crapola work of art, cluelessly assuming that all art was like this.

What most people don’t know about Safer is that he was himself an artist. Or, at least, he made art. In the 1990s I’d heard he made watercolors of motel rooms, and I continuously tried to coax him into allowing me to mount a show of them. I don’t even know if my requests ever got to him, as I never heard from him or CBS. That changed last year, when I was writing an article on art by celebrities, and, after we reached out to him, Safer offered to send a package to New York Magazine.* Before I could say “OMG! The bear is coming out of the woods,” a carefully wrapped bundle of small original works arrived at our offices. I don’t believe they’ve been published, or possibly even seen publicly before.

I didn’t hate them. What I saw had a certain earnest pathos, someone being an artist in a mid-20th-century Sunday-painter way. The work seemed influenced mainly by a very conservative idea about plain modernistic surfaces, depiction, and color. Safer was a careful drawer, and his colors stayed within lines. His subjects were ordinary landscape, portraits, churches, tourist sites, and the like.

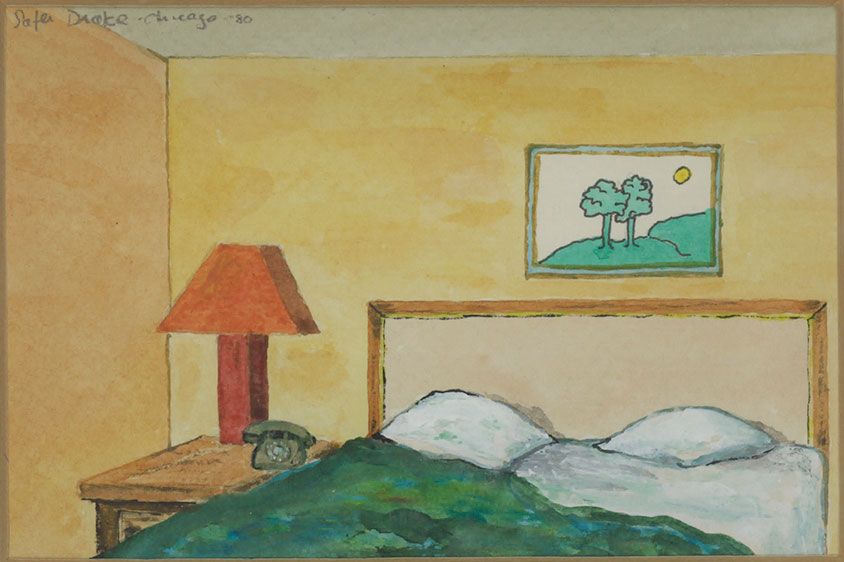

|

| Hotel room, Drake Hotel, Chicago, 1980 Safer was known to paint his hotel rooms while on the road. |

I wouldn’t have bought any of these if I saw them at a yard sale, except one. His motel-room picture has everything you’d want it to have, and even a little bit more. Which is to say banality, blankness, something sweet, neat, forlorn, and soul-killing. The space is cramped, the décor drab and sterile; a rotary dial phone sits on the bare night table next to one generic lamp. Over the small double bed is just the kind of cliché landscape that Safer liked to paint: two trees on a hill with a yellow sun in the white sky. Ironies extend. The rumpled bed with only one side turned down lets us know Safer has been here, alone on the road. A plain poignancy lingers, even in the uninspired style.

In 1990 he painted a native of Burkina Faso, West Africa. He’s black, sitting on the ground against a stuccolike building, and wears some sort of scarlet robe. Never mind the Orientalizing that most in the art world would spot as colonialist, Safer does the whole thing in an unhurried, controlled Gericault-meets-Matisse air.

[Jean-Louis Géricault (1791-1824) was a French painter and one of the pioneers of the Romantic movement. Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was a French painter, regarded as one of the artists who best helped to define the revolutionary developments in the visual arts throughout the opening decades of the twentieth century.]

Another work from the same year finds him giving us a scene overlooking bountiful planted summer fields of musky green. (The guy obviously enjoyed his first-class perks and leisure time.) Other than a great tree that feels like it must have been made on the African serengeti, the rest of the work I saw was typical tourist postcard art. The unhurried arid mise-en-scène conjures sparsely peopled retirement communities built around golf courses.

Adding to the pathos of the pictures, after the article came out and he wasn’t included, I got another email asking me, honestly, why not, and what I thought of his art. I never got back to him. Had I, I would have said that it was too bad he never gave art a real chance, as he seemed to have a real feel for a certain strain of painting from observation. And that, had he not set himself against the whole world of contemporary art, he might have picked up a thing or two that might have helped him.

No comments:

Post a Comment