[As you’ll read below,

my parents had a small art collection, consisting of some 40 oil paintings,

watercolors, prints, sculptures, and a tapestry. When my mother died in 2015 (my father had

died in 1996), the collection was too large for me to display in my New York

City apartment. Shortly after Mom’s

death, I offered the art to my undergraduate alma mater, Washington and Lee

University in Lexington, Virginia, of which my father was a devoted alumnus.

[In

September 2016, the University accepted the loan proposition and on 6 November 2017,

an exhibition of the collection opened in W&L’s Stan Kamen Gallery at the

Lenfest Center for the Arts. After A Passion for Art closed

on 30 June 2018, the collection became available for art classes and rotating display

in various locations around the campus.

(W&L has no permanent art gallery.)]

My

parents collected art from about 1948 to 1995 (see “A Passion For Art: My

Parents’ Art Collecting,” posted on Rick On Theater on 21 November 2017). This activity took off after September 1958,

when, as some readers of Rick On Theater will know, my folks became part

owners of Gres Gallery, a modern-art gallery in Washington, D.C. (see “Gres

Gallery,” 7, 10, and 13 July 2018).

The

gallery closed in 1962, but the art collecting continued until my father’s

death. The art in my parents’ home originated

in many periods (pre-Columbian Mexico, 18th-century Europe, 19th-century China)

and regions of the world (Mexico, South America, the Caribbean, Africa, Europe,

Asia), but the majority of the works are contemporary American painting and

sculpture, including some Native American pieces (Fritz Scholder [1937-2005;

see my post on 30 March 2011]).

Some

of the artists with works in my parents’ collection were longtime friends (Minnie

Klavans [1915-99], Lila Oliver Asher [1921-2021; see my post, 26 September 2014])

and others, like Sam Gilliam and sculptor Leonard Cave (1944-2006), became

friends. Gilliam, 88, died of renal

failure at his Washington, D.C., home on Saturday, 25 June.

Mom

and Dad owned three of Gilliam’s works (and I own one) and they visited the

artist’s home and studio in Mount Pleasant in northwest Washington, D.C., and

the galleries of his partner (since 2018, his wife) and manager, Annie Gawlak.

A

couple of times I accompanied Mom to Gawlak’s gallery at the time, G Fine Art (located

first on M Street in Georgetown and then on 14th Street in Logan Circle; now

closed), just to see what she was showing, and on one afternoon, I went with my

folks to the Gilliam house to chat and see what the artist was working on. I was also visiting my parents on several

occasions when the Gilliams came to their home.

Sam

Gilliam, an African-American painter, was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, on 30 November 1933. He grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, and came

to Washington in 1962. He’s considered part

of the second generation of the Washington Color School, a mid-20th-century (1950s-1970s)

form of abstract art growing out of color field painting which dealt with the

effect of light on color (see my post “The Washington School of Color,”

21 September 2014).

Gilliam

often worked in diverse styles and forms, changing as he discovered new effects

and techniques. The Gilliam I have, Flowers (1989) from the Tulips series, is a mate to one from my

parents’ collection, Petals from the

same series, but the other two in the collection—Chinese, an acrylic work on shaped canvas from 1990, and a small,

untitled, 1995 mixed-media collage on irregular hand-made paper—are different

from each other and from Flowers and Petals.

|

| Untitled mixed-media collage |

Gilliam, prolific and innovative, experimented with many media and varied his application as the medium demonstrated its properties. I went to Sam Gilliam: A Retrospective (see “Awake and Sing!, et al.,” 3 April 2017), an expansive exhibit at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington (15 October 2005-22 January 2006), with my mother, who’d also been invited to the opening, and we found that the show didn’t include any works resembling ours or other pieces I knew Gilliam had made.

For instance, his short 2002 series, Slats,

exhibited at the Marsha Mateyka Gallery near Dupont

Circle (5 April-25 May 2002), was a collection of geometric, brightly

monochromatic, hard-edged constructions the likes of which Gilliam has never repeated.

One afternoon while window-shopping on Wisconsin

Avenue near Tenley Circle, I saw a decorated chair that looked like it had been

painted in the same style as Chinese, the formless canvas of many-colored acrylic

in my parents’ collection.

The piece in the gallery window was an ordinary ’50s/early ’60s style kitchen chair covered with multicolored, thickly impastoed acrylic paint in the same style as the “ribbons” that are woven through the shaped canvas of Chinese. Mother and I agreed that it must be Gilliam’s work, so we asked in the shop and we were right—and yet, the painted chair didn’t resemble Chinese in any other respect.

| Close to Trees at the Katzen Center |

On

another of my visits to Washington, Mother and I drove over to American

University’s Katzen Art Center on Ward Circle to see Sam Gilliam: Close to Trees (2 April-14 August 2011; discussed in “Picasso,

Bearden, Gilliam, and Gauguin,” 26 June 2011), an exhibit of draped nylon and

polypropylene cloths brightly dyed with acrylic colors, especially created for

the Katzen’s third floor. Gilliam had

transformed the space into a forest of color which visitors walked around and past

as if strolling through a grove of trees.

The

artist had worked with draped fabric before—a project in Japan in the 1990s that

led to a site-specific installation of painted cloth at the American Craft

Museum (now the Museum of Arts and Design) in New York City in February-April

1992. The exhibit was accompanied by a

talk on 19 November 1991 on the textile work in Japan that I attended.

Indeed, an increasing amount of Gilliam’s work from the ’70s on was with unframed, unstretched, formless paintings that was distinct from the habitual work created by his fellow Washington Color School artists. He’s often described as having liberated color painting from the flat, two-dimensional format that was the standard among first generation WCS painters.

The drape paintings appeared in Gilliam’s career as early as the 1960s and ’70s, when the artist essentially invented the form. He took the canvas off its traditional stretcher, stained it with vivid colors, and then draped the fabric on the walls, from the ceilings, or over props.

A drape painting is a blend of installation, painting, and sculpture. Each installation is different, and Gilliam is strongly guided by the way the light of the display space plays on the folds of the painted fabric. The element of improvisation, both in the creation and the display of his art, is a great part of what excites me about Gilliam’s work. It evokes Jackson Pollock (1912-56; see “Jackson Pollock: A Collection Survey: 1924-1954,” 4 March 2016) and Morris Louis (1912-62; see “Morris Louis,” 15 February 2010) with respect to Gilliam’s innovative technique.

Though

Louis, a Washington School artist who painted in the ’50s and ’60s, abandoned

stretchers and easels in the mid-1950s, pouring paint directly onto canvases

laid out on the floor of his dining room, he framed the results in the

traditional rectilinear format after he finished the piece.

Annie

Truitt (1921-2004; see “Art in D.C. (Dec. ’09-Jan. ’10),” 18 January 2010),

another first-gen Washington Colorist, abandoned canvas altogether, making

painted wooden columns her signature art form.

Most WCS artists, however, stuck with stretched, usually primed—Louis

worked on unprimed canvas, and Gilliam used unprimed fabrics of various composition—as

their medium of choice.

| Flour Mill at the Phillips Collection |

Gilliam exhibited frequently with galleries across the country (David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles; Pace Gallery, New York and London; Marsha Mateyka Gallery, Washington, D.C.; Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin) and his works are in the collections of many museums around the world.

His first museum show was at the Phillips Collection in 1967; among the other prominent collections that include Gilliam’s work are the National Gallery of Art, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, all in Washington; the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art (see “Spilling Over: Painting Color in the 1960s (Whitney Museum of American Art)” in “Hopper and Turner at the National Gallery & Color Painting at the Whitney,” 23 April 2019), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, all in New York; London’s Tate Modern; and the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris.

While the drape paintings dominated Gilliam’s work in the latter part of his career, he didn’t stick exclusively to that medium. He returned often to draping, but moved into other forms as the impulse stimulated his imagination. He was a lifelong, tireless experimenter. The decorated chair and two of my parents’ three Gilliams—as well as my own piece—are examples of the artist’s flexibility.

|

| Petals at W&L University |

For example, one of Gilliam’s visits to my parents’ apartment was in August 1989. The artist had offered my parents two pieces from his Tulips series, which he described as assemblages on handmade paper with marble, mounted in constructed boxes, in exchange for an investment in the project. My folks were giving me one of the monoprints, so I was present when Gilliam brought the pieces for my parents to see.

Gilliam

himself mounted Petals for my parents

because it takes a special bracket fixed to the wall, onto which fits a wooden flange

on the back of the box frame, which is very heavy because of its construction

and the addition of the marble “appendages.”

(While my piece, Flowers, is square, Mother and Dad’s Petals

isn’t, so mounting it plumb required a sharp eye . . . or a modicum of luck!)

My

dad and I had to install Flowers ourselves when we got it to my

Manhattan apartment. The artist, though,

had thoughtfully made an instructional diagram of the mounting process, adhered

to the back of the wooden box, for this purpose. The print, as Gilliam called these works, has

pride of place in my apartment: on the living room wall directly opposite the sofa.

Flowers is easily one of my

most favorite pieces of art in my own small collection. (Sharing that honor is an Alexander Calder [1898-1976]

lithograph entitled Magie Eolin (1972)—the nearest translation for which

I can come up with is “magic of the wind.”

It hangs opposite Flowers, above the sofa. [See “Calder: Hypermobility at the

Whitney,” 21 August 2017, and “Alexander Calder: Modern from the Start

(MoMA, 2021-22),” 28 January 2022.])

Gilliam

came to my folks’ home again in March 1990 to hang Chinese, an unframed, shaped

canvas with ribbons of painted canvas that must be woven through it. It’s therefore formed differently every time

it’s hung and takes on a completely different character depending on who’s done

the installation.

|

| Chinese |

A

derivative of the draped pieces, Chinese has no predetermined and

immutable shape, no frame, no definitive dimensions, but it’s somewhat more

rigid than the thinner fabric allows the drape painting to be, and has to be

fastened to a wall or panel of some kind.

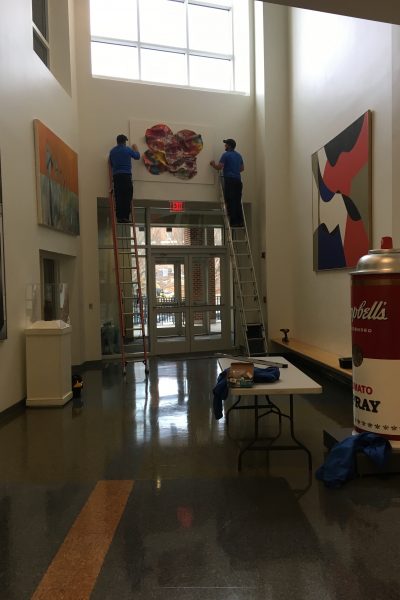

(When the University curator was planning not just the initial exhibit of my folks’ art collection in Lexington, but the eventual display of the artworks in various buildings on the campus, this became a conundrum. W&L is almost 275 years old and there are many buildings on the campus that date back to the days of George Washington; the University doesn’t permit the use of nails on the walls—including the walls of the Kamen Gallery, though for different reasons.

|

| Mounting Chinese at W&L. Note the mounting board. |

(Framed art can be hung in many ways that don’t require putting nails and hooks into ancient plaster walls, but Chinese was designed to be nailed directly to its mounting surface. What to do? I suggested mounting the painting on a board and hanging the backing the way the curator would hang a framed work. I believe that’s what she did.)

Gilliam

returned in the mid-1990s to rehang Chinese—a

title I didn’t even know until the curator of the University Collections of Art

and History at W&L discovered it while mounting the collection for its

introductory exhibit in 2017—when Mother moved to a smaller apartment in her

building.

I

was with Mom and whimsically suggested that the painting should climb up onto

the ceiling—so a lobe reached up onto the ceiling in Mom’s new sitting room. The painting is rather large; unfurled, it’s

approximately 48" x 48".

When

Mom moved to Bethesda in October 2013, I mounted Chinese, under Mother’s direction, in the living room and it

climbed onto the ceiling again, but I wasn’t as pleased with the result as I

had been when Gilliam had hung the work with our input.

(Until

Mother moved to this last residence, which I helped her do, and we transported Chinese

to the new apartment, I never knew what it looked like spread out; it turns

out, the canvas is shaped like a four-leaf clover.)

As

the abstract painting has no pre-established configuration, it will always bear

an imprint of the displayers’ whims and tastes. That’s what delights me about this painting,

making it one of my favorites of my parents’ collection.

What

makes Flowers a favorite in my own collection is that it’s just

different. Nothing else I own is

anything like it—though that’s true of other art I have, too. (For instance, Ossidiana VI [1959] by

Franco Assetto [1911-91] isn’t really a “painting”; the pigment is something

Assetto developed called “aluminum gel,” a chemical compound, the coloration of

which is caused by the different chemicals added to the gel. Aluminum gel is weather-resistant, so some of

Assetto’s works were made for outdoor display.)

Oddly,

the components of the Tulips series are not uncommon in late

20th-century art. Hand-made paper is

very widespread; so is monoprinting. Collages

fashioned from paper which the artist himself has decorated with printing or

painting is a known technique, and so is using paper cut into pieces after

being printed or painted. Box frames for

constructions are fairly common, and so are insertions of various materials.

Still,

no one I knew did all these things in one work of art or did them quite as

innovatively as Sam Gilliam did in Tulips. When I saw Flowers and Petals sitting

on the floor of my parents’ living room, it thrilled me at first glance. I knew immediately that I wanted one of them. My only problem: which of the two did I want

more?

In

the end, my choice was more a whim than a considered decision. I never second-guessed it in the ensuing

years, though. When I die, the two parts

of Tulips that Sam Gilliam gave my folks and me in 1989 will be reunited

at Washington and Lee University since . . . well, who can say how many

decades? Since the artist made them.

No comments:

Post a Comment